Guest post: Leaning In – One Designer And Mom’s View

This post comes to you from our designer par excellence, Kerstin Vogdes Diehn of KV Design, who apart from meditating on “leaning in”, kids, and work, manages to consistently wow us with her design – like with her new website.

Leaning In

By Kerstin Vogdes Diehn

Re-posted from http://kvdesign.net/blog/entry/leaning_in

Jun 09, 2014

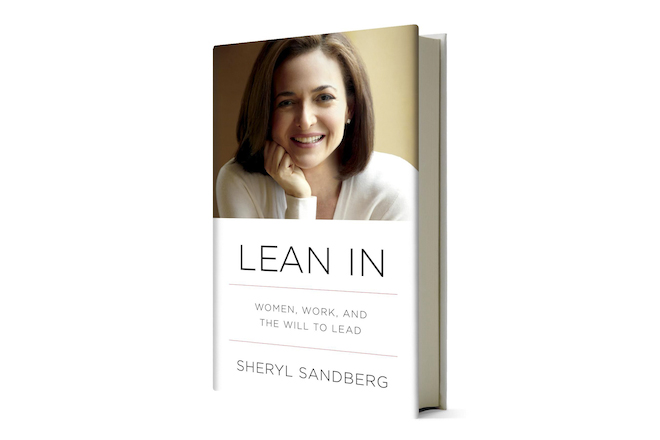

I’m an avid reader, but by and large, I have a strong aversion to business books. They are usually boring, full or nauseating buzzwords or totally inapplicable to my life as a sole proprietor of a design business. So when everyone started talking about Lean In by Sheryl Sandberg, I rolled my eyes and thought, Yuck—I’d never read that. Yet the phrase “lean in” kept creeping up in conversations I had with other professional women. So, I decided to read it and see for myself. Here’s my super unofficial book review…

I’m an avid reader, but by and large, I have a strong aversion to business books. They are usually boring, full or nauseating buzzwords or totally inapplicable to my life as a sole proprietor of a design business. So when everyone started talking about Lean In by Sheryl Sandberg, I rolled my eyes and thought, Yuck—I’d never read that. Yet the phrase “lean in” kept creeping up in conversations I had with other professional women. So, I decided to read it and see for myself. Here’s my super unofficial book review…

I really wanted to dislike this book, but I found myself surprised and compelled by some—not all—of her points. My main critique is that there is a clear assumption that women who can lean in already have the financial resources to do so and are presented with frequent advancement opportunities that they would typically pass by. I’m not sure this is entirely true. Sandberg argues that your partner needs to step up to the plate and lean in more to the family so you have the opportunity to lean in to your job, but given many women’s circumstances, I don’t think this is an option. When your partner makes significantly more money than you, it’s pretty hard to tell that person to step back so you can lean in to your career (especially when you know, like me, that you will never match or surpass his income). Having a husband lean in more at home would be awesome, but it’s pretty much impossible at this point. Also, what if you don’t have a partner? One of my best friends is a professional single mom who is leaning in as much as she can. Who’s supposed to lean in to her family? Again, there are a lot of assumptions of income and circumstance (either you have loads of paid help, or loads of non-paid family help, which you can only afford if you personally are paid a lot of money).

My other major complaint is that to effectively lean in, you do so at the sacrifice of a personal life. Sandberg has made it a policy to be home every night for dinner with her children (yay!), but then after they go to bed, she gets back on the computer and works again (boo!). If you ask me, this is not changing the culture of work to be more suited to women and family, it’s just deferring an already too-demanding work schedule. She describes a perfect day as eating breakfast with her kids, working all day, being home for dinner, and then working again after they go to bed. I was with her until the work after the kids go to bed part. My belief is if we want to change the culture of work to be more female and family friendly, maybe the better thing is to try to convince the powers that be that no one (man or woman) needs to be working a 12-hour day, no matter how that time is carved up. Just ask anyone in Europe. They work a typical 8-hour day and it seems to be working just fine for them. Sometimes I think the smartphone was the worst thing to happen to us—being accessible by clients and business associates at all hours of the day is exhausting and disruptive.

Now, complaints aside, I found myself surprised by some of the facts she presented about women and business. In particular, there was a statistic that struck me. She said that when a job description is posted, women will only respond when they meet at least 90% of the criteria, whereas men will go for it if they only meet 60%. Men have the confidence that they can do the work they don’t know how to do and will be provided with opportunities to learn along the way. Women are more cautious and feel they won’t even be given the chance to try unless they are perfectly qualified. Women thus hold themselves back from challenges and change because they fear they will be rejected or ignored, but often jobs are a lot more than the sum of few posted bullet points.

I really took this point to heart. I often don’t respond to certain RFPs or apply for huge, complex projects because I’m unsure of a couple of the required skills. Yet, I know that I am capable of learning unfamiliar material, and I’m pretty quick about it. I’ve been holding myself back for years for the exact reasons that Sandberg points out. So, after all my blustering and whining, I actually do have a significant positive take away from this book: I’ve decided to lean in to my career more by applying to more proposals and pushing boundaries on potential projects that I otherwise would not have pursued. I’ve already sent out one proposal that a year ago I wouldn’t have considered. If I get it, I’ll send Sandberg a thank you note for encouraging me to lean in. But I’ll also probably have to apologize to my kids as I lean back and work more.